I read Wole Soyinka’s poem, Telephone Conversation when I

was fourteen. I liked it so much I made it the desktop background on my laptop.

Each time I turned on this shiny new device, I would read the words, ‘The price

seemed reasonable, location indifferent. The landlady swore she lived off

premises.’ The poem struck me. Perhaps it was because I was in an English

boarding school, discovering for the first time my ‘blackness.’

‘How dark?’ Soyinka ‘s landlady asked the character who I assumed

was Soyinka himself. ‘Facially, I’m brunette.’ Facially I was... I had never

stopped to consider. I was Nigerian. My classmates, sensitive to but ignorant

of the nature of my dislocation, would sometimes say as if in reassurance, ‘I

think black people are cool.’ Why are you telling me, I would wonder but never

ask?

My spine weakened a little when I moved to England.

Confident, boisterous, perhaps overbearing in Nigeria, I became unsure in England:

unsure of my accent, unsure of the value of what I knew, flabbergasted by my

ignorance of Jack Wills and lacrosse. Soyinka’s poem put some calcium back in

my bones. Every time my eyes wandered to

the bottom of the screen and read, ‘Friction, caused- foolishly, madam- by

sitting down, has turned my bottom raven black,’ I would shake with laughter,

the punch line new again. A new country was to be met with this verve, this

panache, this style, this trademark Soyinka wit. No apologies for where I was coming

from. None at all.

|

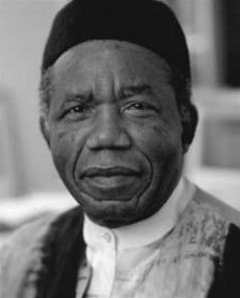

| A young Soyinka, harassed by landladies. |

Telephone Conversation

Wole Soyinka

The price seemed reasonable, location

Indifferent. The landlady swore she lived

Off premises. Nothing remained

But self-confession. “Madam,” I warned,

5 “I hate a wasted journey—I am African.”

Silence. Silenced transmission of

Pressurized good-breeding. Voice, when it came,

Lipstick coated, long gold-rolled

Cigarette-holder pipped. Caught I was, foully.

10 “HOW DARK?” . . . I had not misheard . . . “ARE YOU LIGHT

OR VERY DARK?” Button B. Button A. Stench

Of rancid breath of public hide-and-speak.

Red booth. Red pillar-box. Red double-tiered

Omnibus squelching tar. It was real! Shamed

15 By ill-mannered silence, surrender

Pushed dumbfoundment to beg simplification.

Considerate she was, varying the emphasis—

“ARE YOU DARK? OR VERY LIGHT?” Revelation came.

“You mean—like plain or milk chocolate?”

20 Her assent was clinical, crushing in its light

Impersonality. Rapidly, wavelength adjusted,

I chose. “West African sepia”—and as an afterthought,

“Down in my passport.” Silence for spectroscopic

Flight of fancy, till truthfulness clanged her accent

25 Hard on the mouthpiece. “WHAT’S THAT?” conceding,

“DON’T KNOW WHAT THAT IS.” “Like brunette.”

“THAT’S DARK, ISN’T IT?” “Not altogether.

Facially, I am brunette, but madam, you should see

The rest of me. Palm of my hand, soles of my feet

30 Are a peroxide blonde. Friction, caused—

Foolishly, madam—by sitting down, has turned

My bottom raven black—One moment madam!”—sensing

Her receiver rearing on the thunderclap

About my ears—“Madam,” I pleaded, “wouldn’t you rather

35 See for yourself?”

.JPG)